The Danish Golden Age and National Romanticism

When Danish art became distinctly Danish

J.Th. Lundbye: 'Autumn landscape. Hankehøj near Vallekilde', 1847.

Danish art flourished in the first half of the nineteenth century. That is why the period is generally known as the Golden Age. Talented young men such as Christen Købke, Wilhelm Bendz, Johan Thomas Lundbye, Martinus Rørbye and Wilhelm Marstrand ushered in the new era.

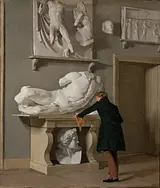

The artists of the Golden Age often looked to their own everyday life for subject matter. Here, Christen Købke has painted ’From the plaster cast collection at Charlottenborg’ in 1839. The cast collection was a regular haunt for him during his time as an art academy student.

At the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen, the professors C.W. Eckersberg and J.L. Lund introduced new teaching methods which meant that students were no longer only taught how to draw after plaster casts of ancient sculptures. Now, the academy offered life classes, allowing students to draw after actual living models, both male and female. The artists would also go on excursions to paint and draw out in the open air. This honed the artists’ sensibilities for depicting the real world more faithfully than before. Everyday life in ordinary Copenhagen homes and life under the open Zealand sky were favourite subjects. However, real life did not make itself too insistently felt at this point: Golden Age pictures tend to depict sunny days and freshly swept streets. Only later in the nineteenth century did the darker and seedier sides of life reach the realm of art.

The nation as subject matter

National sentiments play a major part in Golden Age art, and the Danish landscape became a subject that did more than simply decorate the home: it was also intended to generate pride in the history and unique traits of Denmark. In a similar vein, there was great interest in national and regional costumes and in Norse mythology and popular legend, which were seen as evidence of Denmark’s deep roots in the rich soil of history.

This process of national revival had far-reaching consequences for those Danish artists who were inspired by art from abroad, particularly from German-speaking regions. Their works were consigned to obscurity and have only begun to re-emerge in recent years . The Hirschsprung Collection reflects this tendency. While the museum is full of works by Danish artists with a national outlook, it contains only few paintings by Golden Age painters who looked to German-speaking regions for inspiration, such as Ditlev Blunck and his teacher, J.L. Lund, who was not added to the museum collection until 2017.

The nation as subject matter

National sentiments play a major part in Golden Age art, and the Danish landscape became a subject that did more than simply decorate the home: it was also intended to generate pride in the history and unique traits of Denmark. In a similar vein, there was great interest in national and regional costumes and in Norse mythology and popular legend, which were seen as evidence of Denmark’s deep roots in the rich soil of history.

This process of national revival had far-reaching consequences for those Danish artists who were inspired by art from abroad, particularly from German-speaking regions. Their works were consigned to obscurity and have only begun to re-emerge in recent years . The Hirschsprung Collection reflects this tendency. While the museum is full of works by Danish artists with a national outlook, it contains only few paintings by Golden Age painters who looked to German-speaking regions for inspiration, such as Ditlev Blunck and his teacher, J.L. Lund, who was not added to the museum collection until 2017.

J.Th. Lundbye’s ‘Autumn Landscape. Hankehøj near Vallekilde’ from 1847 is dominated by strong winds that create the kind of weather typical of Danish Septembers, bending trees and shrubs.

Johan Thomas Lundbye was one of the pre-eminent artists of the Danish national movement. In his painting from Hankehøj he merges past and present in a depiction of a Zealand landscape. The burial mound serves as a reminder of the nation’s proud ancestors, as described by the poet Adam Oehlenschläger in the song that became the national anthem of Denmark, 'Der er et yndigt land' ('There is a Lovely Land'):

"There in the ancient days,

the armoured Vikings rested

between their bloody frays.

Then forth they went the foe to face,

now find in stone-set barrows

their final resting place."

The present day depicted in Lundbye’s picture is no less noble: we see a pure-hearted shepherd, descendant of the proud, free people of the past and part of the agricultural sector that was so important to Denmark’s economy and identity.

Discovering Jutland

In 1830 it became possible to sail from Copenhagen to Aarhus by steamboat, and this service proved vital to the artist community’s discovery of Jutland. Initially, the artists would mostly depict the coastline of eastern Jutland, clad in beech woods. However, they gradually ventured further west, causing impressions from the forests around Silkeborg and the Jutland moors to emerge in sketchbooks and paintings. The new focus on Jutland did not only reflect the artist’s willingness to seek out new subject matter, but also a steady rise in national sentiment. In the wake of the Napoleonic Wars, which had rearranged the national borders on the continent, every nation in Europe was keenly interested in defining its very own heart and soul, its distinctive national traits. In Denmark this issue took on extra urgency when the nation’s southern borders were challenged by Prussia, first in 1848 and with particularly disastrous results for Denmark in 1864, when the nation lost the duchies of Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenborg.

Discovering Jutland

In 1830 it became possible to sail from Copenhagen to Aarhus by steamboat, and this service proved vital to the artist community’s discovery of Jutland. Initially, the artists would mostly depict the coastline of eastern Jutland, clad in beech woods. However, they gradually ventured further west, causing impressions from the forests around Silkeborg and the Jutland moors to emerge in sketchbooks and paintings. The new focus on Jutland did not only reflect the artist’s willingness to seek out new subject matter, but also a steady rise in national sentiment. In the wake of the Napoleonic Wars, which had rearranged the national borders on the continent, every nation in Europe was keenly interested in defining its very own heart and soul, its distinctive national traits. In Denmark this issue took on extra urgency when the nation’s southern borders were challenged by Prussia, first in 1848 and with particularly disastrous results for Denmark in 1864, when the nation lost the duchies of Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenborg.

P.C. Skovgaard was among the artists who ventured west and found new artistic subjects in Jutland. Here he has painted a 'View of the Vejle Valley' in 1852.

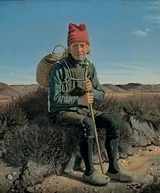

Folk scenes became a favourite motif in the mid-nineteenth century because of the growing interest in the lives of ordinary Danes and the soul of the Danish people as such. Artists such as Frederik Vermehren, Christen Dalsgaard and Julius Exner depicted scenes showing regional costumes and rural customs. They were not always painstakingly accurate while working; for example, they might mix up regional costumes from different areas. Nevertheless, their pictures do provide some impression of a world that was already disappearing with the onset of industrialisation. The Golden Age was coming to an end; now, art was to be something more and other than simply national in scope, and the time was ripe for Naturalism to enter the stage.

In this 1851 painting, Fr. Vermehren depicts a figure that could be found only in thinly populated areas: an itinerant bread seller. He is shown here taking a moment’s rest on the Jutland moors.